Chapter 1 Notre-Dame: the experience of a total art

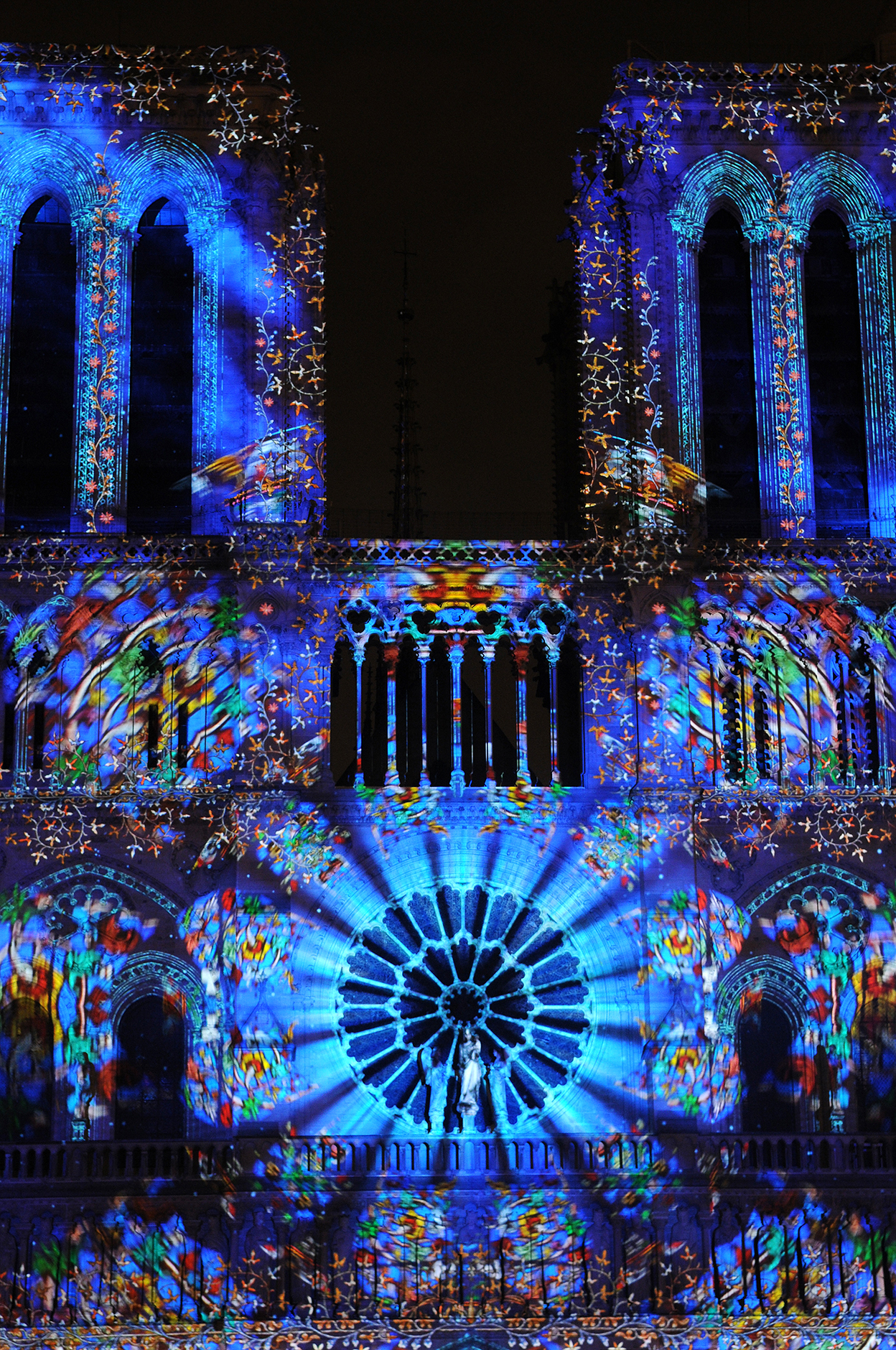

Notre-Dame de Paris 2017. Bruno Sellier - Author and scenographer. Spectacular, Allumeurs D'images - Creation © Jean-Marc Charles, 2017.

Notre-Dame de Paris 2017. Bruno Sellier - Author and scenographer. Spectacular, Allumeurs D'images - Creation © Jean-Marc Charles, 2017.

Notre-Dame de Paris 2017. Bruno Sellier - Author and scenographer. Spectacular, Allumeurs D'images - Creation © Jean-Marc Charles, 2017.

Martin Monferran, Claudie Voisenat

Viollet-le-Duc was still a very young child, perhaps 3 to 5 years old, when the old servant of his family took him to Notre-Dame. "The crowd was large, the cathedral was covered in black. My eyes were fixed on the stained glass windows of the southern rose, through which the sun's rays passed, colored in the most brilliant shades [...]. Suddenly the great organs were heard; for me it was the rose that I had before my eyes that was singing [...] I came to believe in my imagination that such and such a panel of stained glass windows produced low-pitched sounds, such and such a high-pitched sound, I was seized with such a beautiful terror that I had to get out of the room. The future restorer of Notre-Dame thus had his first experience of art. An experience which is, for him, polysensorial by nature, since art is a single source divided into multiple expressions and that "the artist, whoever he may be, poet, musician, architect, sculptor or painter, strikes on the same cord of the soul" (Entretiens sur l'architecture). He undoubtedly also experiences the sacred, as defined by Rudolph Otto, a source of both terror and fascination.

Even today, it is by calling upon all their senses that visitors to the cathedral describe their attachment to the building, the aesthetic experience they have had. They evoke the soft, almost pink light of the late afternoons on the façade, the dark coldness of the interior illuminated by the large roses, the beauty of the place as if exalted by the sound of the bells, the organs or the chants. One of them, when asked what he would like to find when the cathedral is restored, answers: "The old stones that we could save of course, but will there be any soul left? The colors of the stained glass, the muffled sounds. The smell will inevitably be gone."

Chapter 2 On the scale of a human life: another authenticity

Notre-Dame in winter. © Guilhem Vellut, Creative Commons, CC BY 2.0, février 2016.

Notre-Dame in the spring. © Ewcia2331, Creative Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0, 13 avril 2019.

Souvenir photo in front of Notre-Dame de Paris. © Gary Todd, Creative Commons, CC0, juillet 2016.

Martin Monferran, Claudie Voisenat

Heritage professionals tend to consider authenticity according to the criteria of art. Between the Italian Renaissance and the 18th century, a new definition of the work of art was established, characterized by its absolute singularity. In this context, the question of authentication becomes central, whether it concerns its author (with the signature), its origin, its location in time, its manufacturing process or its conservation in relation to its original state. In short, on the elements that distinguish the work of art and that set it apart. This form of authenticity is essentially attached to the form and the material.

But other forms of authenticity are possible. In law, for example, a copy can be authentic if it is certified to be a true copy of the original. To rebuild identically, by finding the materials and the techniques of origin, can thus be assimilated to a form of authenticity. In this case, it is not the building in its form and its material that proves to be authentic, but the process that presided over its reconstruction.

Finally, for most heritage users, authenticity is not only linked to scholarly criteria, but also to the memories that are attached to the monument. Indeed, monuments are not only places where memory is embodied; the monument produces memory, it is inscribed in individual histories, we remember what we felt there: a feeling of grandeur, of eternity, of being rooted, of spiritual elevation, of being at the heart of history, connected to the past, of being part of the lineage of men and builders... There are countless ways to experience Notre-Dame, but it is always a question of the effect it produces on the spirits. Far from the material, authenticity here is about mental and spiritual dimensions, about fidelity to the impressions left, to the moral, intellectual or artistic influence of the work. Here, authenticity reaches its philosophical meaning of deep value in which a being expresses its personality, manifests and singularizes itself.

Notre-Dame, often described as a loved one, an elderly lady, a family member or a close friend, is indeed endowed with a personality - some say a soul - and an influence that she exerts singularly on everyone. It is to this deep truth that her visitors want her to be faithful.

Chapter 3 Liturgies, silent presence of the density of faith

Chimeras © Benjamin Mouton

Religious office © Benjamin Mouton

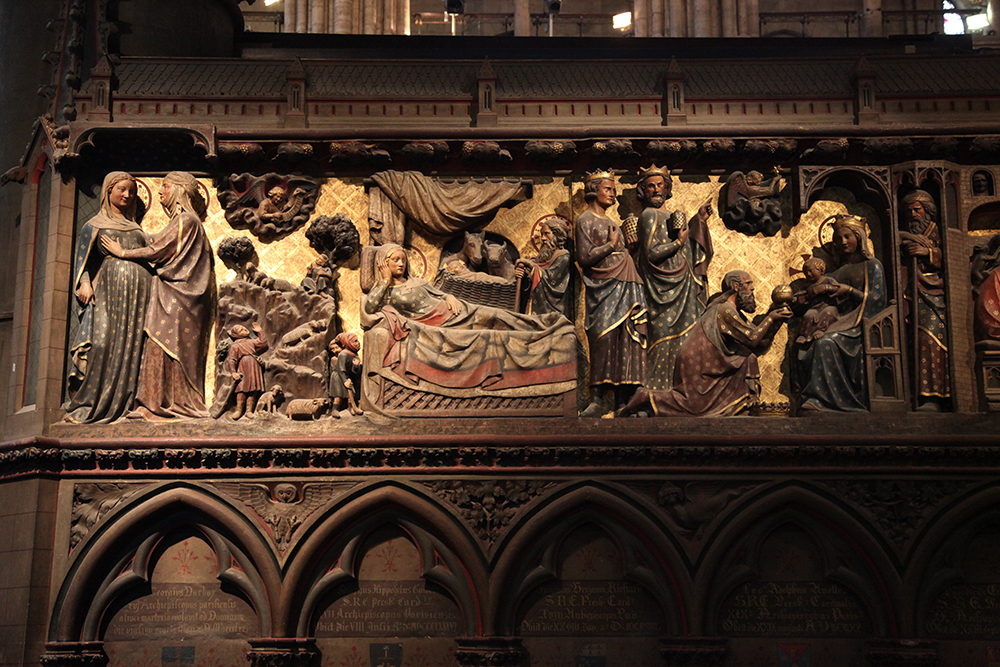

Holy story around the choir © Benjamin Mouton

Benjamin Mouton

A Catholic architecture

The cathedral was the expression of an epic of the Middle Ages, exalting a triumphant and joyful religious renewal, a New Church. The architecture of Notre-Dame writes it from the western facade, its statuary, from the portals to the chimeras and fantastic figures perched on the heights, which tell of the perils of the world in ambush.

The "salvation" is inside; the magisterial volume draws the gaze towards the sanctuary, the altar, and throughout the wandering of the aisles, tells the holy story... For the world of believers, the place is naturally inspired.

Sacredness of place

For the lay visitor, or stranger to this confession, the sacredness of the place imposes itself not only by the effect of the majesty, of the grandiose scale that imposes itself, of the lights, of the sounds... but also, and perhaps above all, by the effect of an insensible and mute density, the breathing of the walls, of the stones and of the vaults, which seizes and upsets and which each one perceives in spite of himself.

And it is this virgin sensibility, innocent of any added culture that is undoubtedly the most significant revelation of the sacredness of the place, a sacredness that comes from the depths of history, where pagan and archaic mysteries intersect, which have shaped and still inhabit the human soul.

Paradox of the Architecture which says more than expected...

Secularity of the work

As early as the 13th century, the master builder was a layman mandated by the clergy to build cathedrals: Amiens, Paris, Reims, Strasbourg... attest to this, and their masterpieces seem to suggest that the most effective way to serve the "cathedral program" is to be a stranger to its vocation.

Viollet-le-Duc was a layman, and so were many of his colleagues and successors. By extension of the time of the builders, is it necessary to be a layman to devote oneself, without any other influence since it is architecture which must command the conservation of this religious heritage?

Paradox of the Architect inhabited by the work...

Fervor © Benjamin Mouton

Sacredness of the place © Benjamin Mouton

Majesty of the architecture © Benjamin Mouton

Interior density © Benjamin Mouton

The lay master of the work, between the monk and the soldier. Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionary (coll. part)

A controlled and balanced architecture © Benjamin Mouton