Chapter 1 Restoring acoustics and soundscapes

Sound recording in Notre-Dame de Paris before the fire, in April 2015. © Peter Stitt & Brian FG Katz, CNRS, 2015.

Sound recording in Notre-Dame de Paris after the fire. © Christian Dury, Chantier CNRS, Notre-Dame, Groupe Acoustique, 2020.

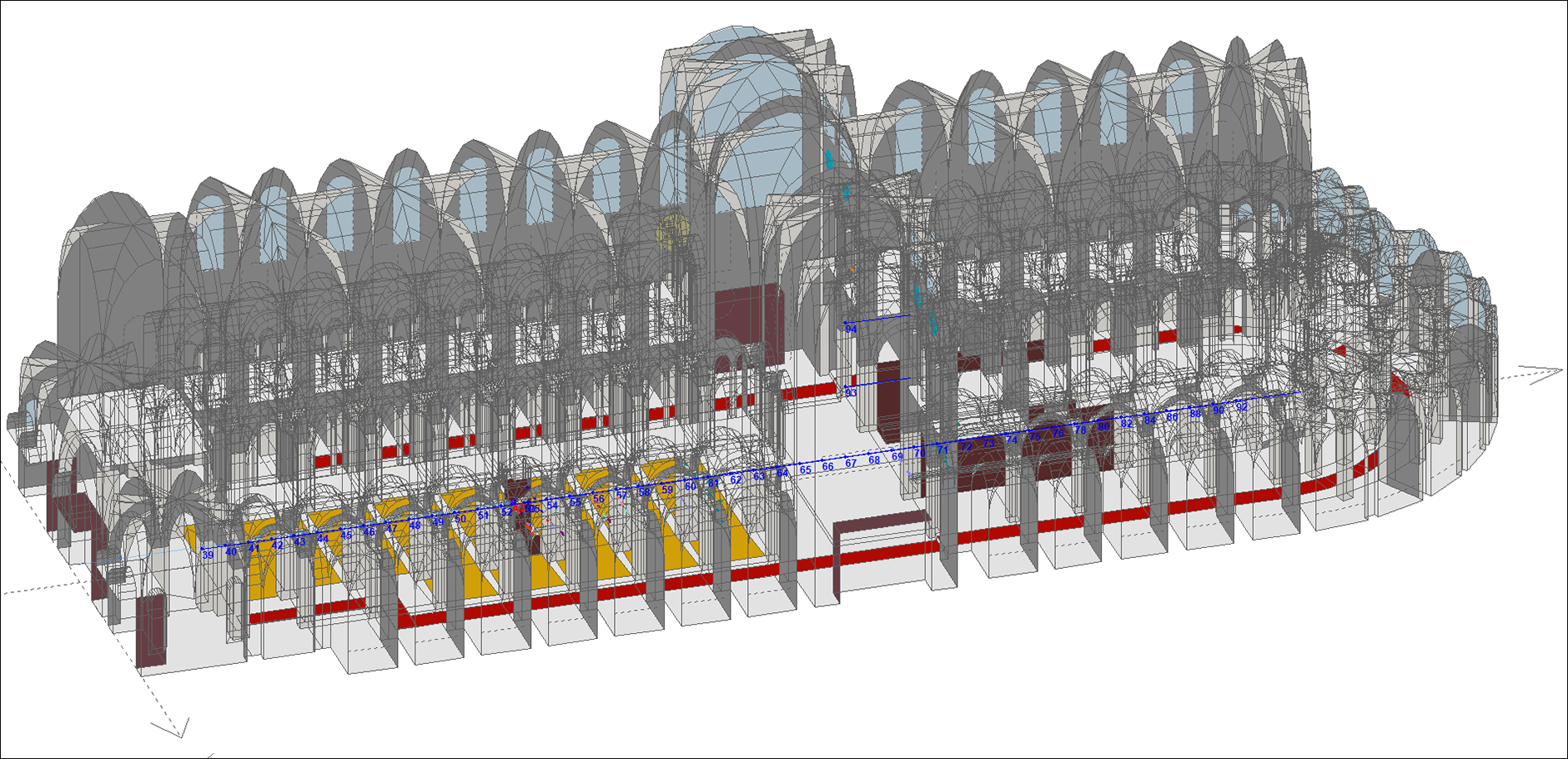

Digital acoustic model of the cathedral. © Bart Postma & Brian FG Katz, Chantier CNRS Notre-Dame, Group Acoustique, 2020.

Brian Katz

The fire of the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris has highlighted the fragility of the acoustic heritage. The acoustics of a site, if it has an immaterial dimension, depends above all on the building and the layout of the space. It is paradoxically ephemeral, although it is the product of its immediate physical environment. Acoustic measurements, simulations and digital reconstructions offer the possibility of documenting the acoustics of sites such as Notre-Dame de Paris, while allowing scientists (acousticians, archaeologists, historians, musicologists, etc.) and the general public to explore and discover lost acoustics.

Despite the interest in it, little data has been collected on the acoustic parameters of Notre-Dame de Paris, and these do not agree. Sound recordings dating from 1987 were recovered and in 2015, a new series of recordings was made. The comparison of the results of these two sessions shows that before the fire, the reverberation time in the cathedral tended to decrease slightly (8%). Finally, other measurements carried out in 2020, as part of the restoration work, show that the reverberation time has significantly decreased (20%) since the 2015 study. As recent studies have proven that numerical simulations and perceptual analysis are reliable methods to understand complex acoustic conditions, a geometric-acoustic model for computer simulation of the Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral has been developed from the 2015 measurements. Used as a reference point, this model can be used to examine the impact of the fire with more recent measurements, but also to anticipate the outcome of certain decisions made during the restoration, concerning materials and finishes - among other elements affecting the acoustics of the cathedral. The acoustic model can thus be used to study possible evolutions during the reconstruction.

In addition, an ongoing survey is soliciting input from clergy, organists, and choir members to understand how these different actors perceived the acoustic qualities of the cathedral before it burned down, with the goal of identifying the ideal acoustic conditions to guide the restoration. Indeed, the acoustics of the cathedral evolve continuously over time, due to reconfigurations of the space and works carried out inside the building. In this context, the acoustic model can also be used to explore the evolution of the cathedral's acoustics since its construction, more than 850 years ago. Many elements of the cathedral have evolved, due to the various architectural renovations, to the damages that occurred during the French Revolution, or to the variations in the decorations used for certain religious or political events. The acoustics of Notre-Dame de Paris, which vary according to the season, have never been a constant in history. On the contrary, it is an immaterial object, which evolves according to its environment and human occupation. Combined with the work of historians, the acoustic model and the sound simulations it produces allow us to explore and experience these earlier states of the cathedral's acoustics.

Chapter 2 Making the organs sound

The choir organ and the stalls designed by Robert de Cotte (18th century) seen from the gallery. © Myrabilla, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0, février 2013.

The great organ of Notre-Dame de Paris. © Frédéric Deschamps, Wikimedia Commons, Domaine public, octobre 2006.

Isabelle Chave

The restoration of the Paris cathedral also includes the restoration of its organs.

As early as 1198, the use of an organ is attested to in the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris, which today has two instruments: one in the gallery and one in the choir. Since the beginning, for liturgical accompaniment and cultural animation, fifty titular organists have succeeded each other on the gallery. At the time of the fire in 2019, the three titular organists of the gallery organ were added to the two titular organists of the choir organ.

In 1403, a large Gothic organ was built on the gallery that houses the current instrument. This large medieval organ had an exceptional longevity: it sounded for more than three centuries. In 1730-1733, the organ was rebuilt in a classical style with a majestic case. During the great work of the architect Viollet-le-Duc, the organ builder Aristide Cavaillé-Coll conceived a very large symphonic instrument placed in the monumental 18th century case. The project was presented at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1867, before its inauguration. Modifications were made throughout the 20th century to this instrument, which was much in demand for religious and cultural purposes. For the 850 years of the cathedral, a new campaign allows to inaugurate, in 2014, an instrument made up of 115 stops and 7952 pipes, distributed on 5 keyboards of 56 notes and a pedalboard of 30 notes.

The choir organ dates from the 19th century. There were first two organs, built in 1841 and 1844, and replaced by a new instrument installed in 1863 by the architect Viollet-le-Duc above the choir stalls, in a neo-gothic case that he designed. Completely rebuilt in 1911, it again required a major restoration in 1966 and was judged to be unsalvageable. A new instrument was created by the organ builder Robert Boisseau, replacing the original case and a few wooden pipes from 1911. The construction work was completed in May 1969. Regularly maintained and used on a daily basis, it was completely rebuilt in 2010.

During the fire of April 15, 2019, lead-laden soot was deposited in both instruments. At the beginning of August 2020, the console of the great organ was removed and the dismantling of its 8000 pipes was completed on December 9, 2020. The choir organ, sprinkled with water to preserve the choir stalls and with runoff from the vaults, was severely damaged: only 90% of the metal pipework and the woodwork of the case could be reused; the console, the wooden pipework and the blower and transmission system could not be used again.

Chapter 3 The Choir of Notre-Dame de Paris

Adult choir of the Notre-Dame de Paris choir school, October 22, 2017 © Léonard de Serres, 2017

Christmas concert at Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, December 24, 2020 © Henri Chalet, 2020

Isabelle Chave

The Maîtrise Notre-Dame, which was created in the 12th and 13th centuries at the same time as the cathedral, is the guardian of an extraordinary intangible musical heritage. It is administered by the association Musique Sacrée à Notre-Dame de Paris, which is responsible for all the musical services and federates multiple musical activities in the cathedral. The school, which welcomes children and adults, provides a complete teaching program in solo and choral singing, from initiation to professional training. Drawing its singularity from the diversity of the disciplines taught and the repertoires covered, the choir school has conducted important research on the Gregorian repertoire and medieval music, and on their relationship with architecture. The acoustics are not uniform throughout the building; the choirs can search for different sound planes by moving around, working on the notion of "spatialization" of the music. They can also play with the statuary and place themselves in front of a particular work, depending on the pieces in the repertoire.

It was on Sunday, April 14, 2019, for the Palm Sunday Mass, that the Choir sang a final Stabat Mater. This century-old institution was deeply affected by the fire that occurred the next day, which was compounded by the financial difficulties induced by the pandemic. A few months after the fire, the association Musique Sacrée, which had about sixty employees, had to let go of 80% of its staff.

Since the fire, only three ceremonies, without an audience, have been organized in the cathedral. The choir returned to the building only for the Christmas holidays in 2020, for a concert with its director and eight singers, accompanied by the organist Yves Castagnet, at the keyboard of a positive organ brought in for the occasion, the soprano Julie Fuchs and the cellist Gautier Capuçon.

The Maîtrise is the heir to the knowledge and skills of the choirmasters of Paris Cathedral in the Middle Ages, from the polyphonists Léonin and Pérotin in the 12th and 13th centuries. Gregorian chant has a very important place in the training of the Maîtrise, the only group in France to bring it to life; but its repertoire also covers 800 years of music. With a musical repertoire as old as the stones of the cathedral and celebrated for the quality of its pedagogical project and its investment in the transmission of choral singing, the choir will only be able to fully revive its intangible heritage if it regains access to its natural practice environment.

Chapter 4 The stained glass windows and the light

Interior view of the north rose of the north arm of the transept and the skylight left by the collapse of the vaults of the transept crossing. © Dominique Bouchardon, LRMH, 21 juin 2019.

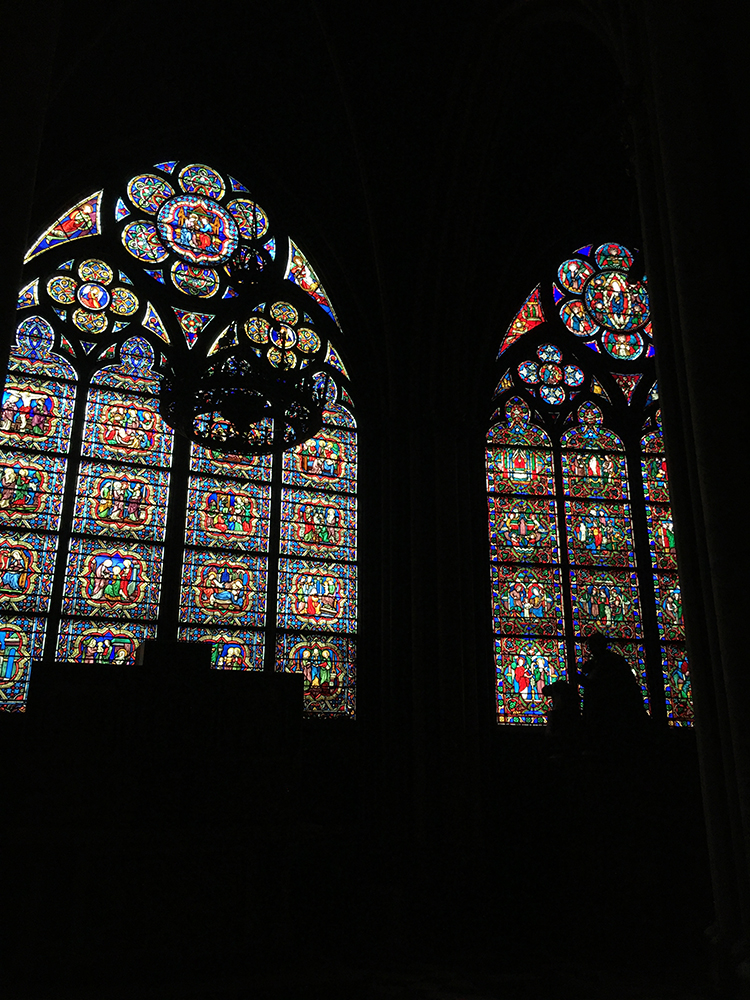

Stainedglass of one of the choir chapels, Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral. Detail: legend of Saint Hubert. Right stained-glass window of Saint-Georges chapel, Notre-Dame de Paris © Vassil, Creative Commons, 19 décembre 2008.

Paris, Notre-Dame cathedral, observation of the western rose by the team of the Laboratoire de recherche des monuments historiques (LRMH). © Alexandre François, LRMH, 14 juin 2019.

Claudine Loisel

When the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris burned, all the stained glass windows were preserved. From the next day, a new look can be taken on these stained glass windows, illuminated by both transmitted and reflected light coming from the luminous crater dug at the crossing of the transepts by the fall of the spire. The catastrophe, materialized by the collapse of a part of the vaults, the cascades of molten lead and the blaze of the framework, is followed by a source of dazzling and colored light through the intact stained glass windows.

Stained glass is a French art form that combines different materials: colored glass, lead and opaque or translucent paints. Without light, a stained glass window is extinguished, it does not vibrate. The variations in light create a perpetual movement of these works of art. In a way, the light offers, by the reflections that it diffuses, a third dimension to the stained glass. If restoring materials is a crucial and delicate step, requiring the skills of experts, the anticipation of the rendering of this immaterial force that is the flow of colored light must be taken into account from the beginning of the restoration. Which luminosity does Notre-Dame wish to have: the intense and colored light of the 12th and 13th centuries, or the more attenuated light of the 19th century? In the 19th century, the use of patina on all the stained glass windows was frequent to darken the buildings and thus allow the faithful to meditate.

One of the riches of the cathedral Notre-Dame de Paris lies in the variety of its stained glass windows, created at different times: it has a collection ranging from the 12th to the 20th century, through the 13th, 14th, 16th, 18th and 19th centuries. Notre-Dame is a true reflection of the history of the art of stained glass in France. Without knowing it, the visitors and the faithful are impregnated with this colored light, carrying, through the stained glasses, more than 850 years of history. These major works and the light they produce, inherited from our predecessors, must be restored and preserved as respectfully as possible, according to the rules of ethics, to be passed on to future generations.

Chapter 5 Lights of day and night, the mystery of Notre-Dame

Daylight at Notre-Dame © Benjamin Mouton

Grisaille window in the chapels © Benjamin Mouton

Grisaille window in the choir chapels © Benjamin Mouton

Stained glass windows in the axis bays © Benjamin Mouton

Benjamin Mouton

Gothic light

The Gothic architecture is that of the light: it is indeed by the unloading of the walls allowed by the crossing of ogives that allowed the opening of the windows to receive large colored stained glass. The art of stained glass blossoms and knows its great hours. As early as the 12th century, Notre-Dame contributed to this evolution, and the lengthening of the high windows at the beginning of the 13th century amplified the light program.

Alterations

At the beginning of the 14th century, the high windows of the choir began to be replaced by clear windows, followed by those of the lower chapel until the middle of the 18th century: there was a break with the spirit of the Gothic architecture.

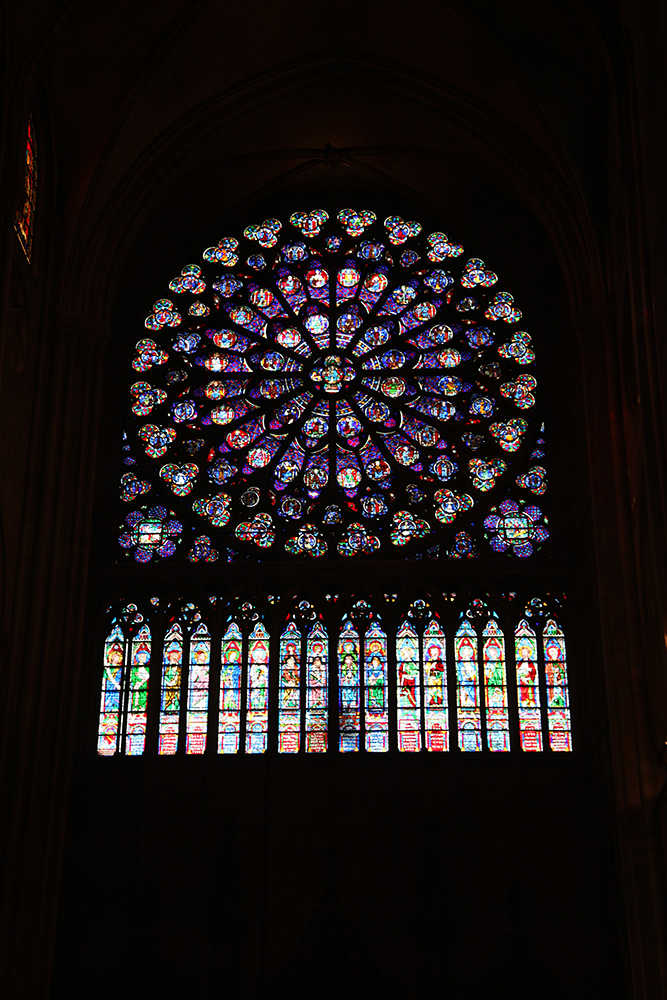

Miraculously, during the fire, the three rose windows were spared.

And restoration

Inspired by the 13th century stained glass windows preserved in other cathedrals and the rose windows still in place, Lassus and Viollet-le-Duc restored the Gothic light according to a homogeneous and rigorous program, based on a chromatic progression towards the sanctuary, and staggered towards the high bays.

Below: the windows of the chapels of the aisles and the ambulatory are made of clear glass, grisailles and colored borders; but in the three chapels of the ambulatory, they are decorated with medallions in the intense coloring of the 13th century.

Above, the stained glass windows of the tribunes, responsible for illuminating the nave and the choir, are filled with identical clear glass. The upper level is decorated with clear glass in the nave, but in the choir, stained glass windows with large figures, geometric and plant motifs brightly colored.

Attentive to respecting the characters of the stained glass of the 13th century, the scale of glasses and lead, the sobriety of the grisailles and the saturation of the colors, in resonance with the natural hierarchy of the architecture and the liturgy, Lassus and Viollet-le-Duc restored thus the Gothic light for which the architecture calls, and which projects on the walls and the polychrome decorations, of the living mosaics of colors.

All the windows are still in place, but in the high nave, they have been replaced by contemporary windows, without a break in scale or coloring.

Daylight, night light

There is a daylight, according to the hours of the sun, and a night light: in the 19th century, the nave and the choir were lit by large chandeliers coming down from the high vaults, and completed at the crossing by the masterly "crown of light", strongly punctuating the enfilade of high arches at the entrance of the choir. In the aisles, sconces distributed a more discreet light: a hierarchy of spaces and time.

The chandeliers have been moved to the large arcades; the crown of light is in exile in Saint-Denis; the gradual increase in the intensity of the interior light has broken the subtle balance between day and night.

Mystery of Notre-Dame

Since the fire, a raw and white light falling from the collapsed vaults floods the interior of the cathedral, upsetting with an unexpected violence all this balance of the architecture with its light. Paradoxically, one could hear comments rejoicing in this light revealing the details of the construction. But architecture is not limited to construction...

The proof is in the pudding: In Notre-Dame, along with the sounds and smells, the harmony of light and color is a fundamental component of the architecture. It is part of the "Mystery" of the cathedral, one of its essential intangible values that must be faithfully restored.

Glass of the tribunes © Benjamin Mouton

South rose © Benjamin Mouton

Choir © Benjamin Mouton

Modern glass windows in the nave © Benjamin Mouton

Chandeliers in the large arcades © Benjamin Mouton

Shadow in the aisles © Benjamin Mouton

Intense illumination of the cathedral © Benjamin Mouton

Mystery of Notre-Dame © Benjamin Mouton